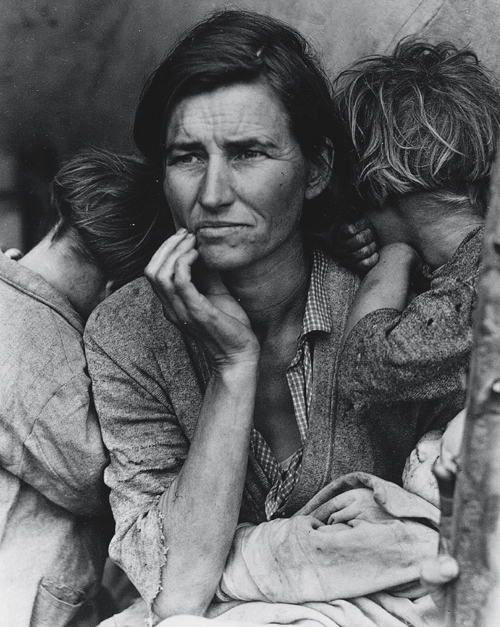

‘Migrant Mother’, Nipomo, California, 1936. Photographed by Dorothea Lange

Over the next few months I’ll be writing a series of articles about some of the most iconic images taken throughout this and the last century, images that have made a real impact to us, the viewer. Some of the images are well known, others maybe less so, but behind every image there is a story about the subject or the photographer who took it – and it’s that aspect I’ll be exploring.

For the first photograph in this series I’ve chosen a portrait with a fascinating story behind it. It was captured in 1936 by the American photographer Dorothea Lange, and it’s a close up of a poor migrant mother taken in the middle of the Great Depression in America. It’s an image I’ve known and loved for years, and is, in my opinion, every bit as good as any classic oil painting.

The woman’s name was Florence Owens Thompson and she was staying in a temporary camp set up for pea pickers – but I’m getting ahead of myself so let me start at the beginning. The early 1930’s was a tough time for many Americans; the stock market had crashed and thousands of people were on the move, looking for any kind of work they could find. The other major catastrophe to hit the western states was drought, with the hopes and dreams of many farmers and sharecroppers blown away.

It was in this climate of desperation and poverty that President Roosevelt set up a programme to help and support farmers and migrant workers. The Farm Security Administration (FSA) was set up to help resettle farmers and also document the plight of the poor migrant workers. A charismatic man called Roy Stryker was put in charge of documenting the FSA’s activities and he knew how well the power of the photographic image could be used to the organisation’s advantage. He commissioned a list of well known photographers to go into the field and they included Walker Evans, Ben Shahn and Jack Delano to name a few.

In 1935, Dorothea Lange was working for the Rural Rehabilitation Division in California as a photographer. The San Francisco News published her first photographs in early 1936 and they shocked the viewer; the images were of people living in sheer poverty, but it was one particular image that made her famous.

She had been travelling around California, for about a month by herself, shooting the working and living conditions of the migrant communities. Her work was done and she had packed her car and was on her way home to see her family, but on the drive home on Route 101 she saw a sign on the side of the road saying ‘Pea Pickers Camp’. She didn’t go to it straightaway, in fact she drove on for another 20 miles before her conscience made her turn back to the camp. Here is her own account of how the portrait came about:

“I saw and approached the hungry and desperate mother, as if drawn by a magnet. I do not remember how I explained my presence or my camera to her, but I do remember she asked me no questions… She told me her age, that she was 32. She said that they had been living on frozen vegetables from the surrounding fields, and birds that the children killed. She had just sold the tyres from her car to buy food. There she sat in that lean-to tent with her children huddled around her, and seemed to know that my pictures might help her, and so she helped me. There was a sort of equality about it.”

Florence Owens Thompson had seven children to feed, and the reason the family was in the picker’s camp was because their car had broken down and they had coasted to a stop just inside it. It was while her husband and two of her sons were away sorting out the car that Lange arrived and shot the images.

The series of images taken that day were used to define the whole plight of migrant workers. Roy Stryker called Migrant Mother the “ultimate photo of the depression era”. The great Edward Steichen said the images were “the most remarkable human documents ever rendered in pictures”. Praise indeed, but the story didn’t end there.

Florence claimed that she had asked Dorothea not to publish the photos of her and her children and she also asked Dorothea for some copies, but she never received them. The image was published and because of it, relief to the tune of $20,000 was sent to the camp to help the 3,000 people living there. By then, however, Florence and her family had moved on.

Florence’s family were tracked down in the late 1970’s and they were still bitter about the way her image had been used. When interviewed, Florence said, “I wish she [Lange] hadn’t taken my picture. I can’t get a penny out of it. She didn’t ask my name. She said she wouldn’t sell the pictures. She said she’d send me a copy. She never did”. In 1998 a copy of the image was sold for $244,500 by Sotheby’s New York. In 2002 another copy was sold by Christie’s New York for $144,500.

In her defence, Dorothea Lange must have taken photos of hundreds, if not thousands, of ‘unknown’ people during her time with the FSA. This image did exactly what Roy Stryker wanted it to do: it brought poverty to the eyes of the people it was intended for and galvanised their help and support in raising the relief money that was needed at the time.

That the image of Florence became – and will always be – ‘the’ image of the Great Depression was more by luck than judgement. The photographers working for the FSA in the Depression shot a total of 3,500 negatives, and any one of them may have been the ‘one’. In 1998 the US Postal Service even used the image on a 32c stamp. Dorothea Lange continued her distinguished career eventually joining a steller group of photographers that included Ansel Adams, Minor White and the rather eccentric Imogen Cunningham as faculty at the Fine Art photography department at the California School of Fine Arts.

I’ve met a lot of people who say that you can’t define someone in one image. I disagree here; the image of Florence Owens Thompson shows quite eloquently a mother’s worry and fear about herself, her family and her uncertain future. I consider this image to be one of the finest portraits taken in the 20th century and I will continue to look at it over the coming years, just as I’ve done for the past 40. It will always make me think about the plight of those dispossessed people, living through one of the most difficult times in American history.