Translated from Italian, ‘Gli isolani’ literally means ‘the islanders’. But of course, like all of editorial and fine art documentary photographer Alys Tomlinson’s projects, it’s about much more than that.

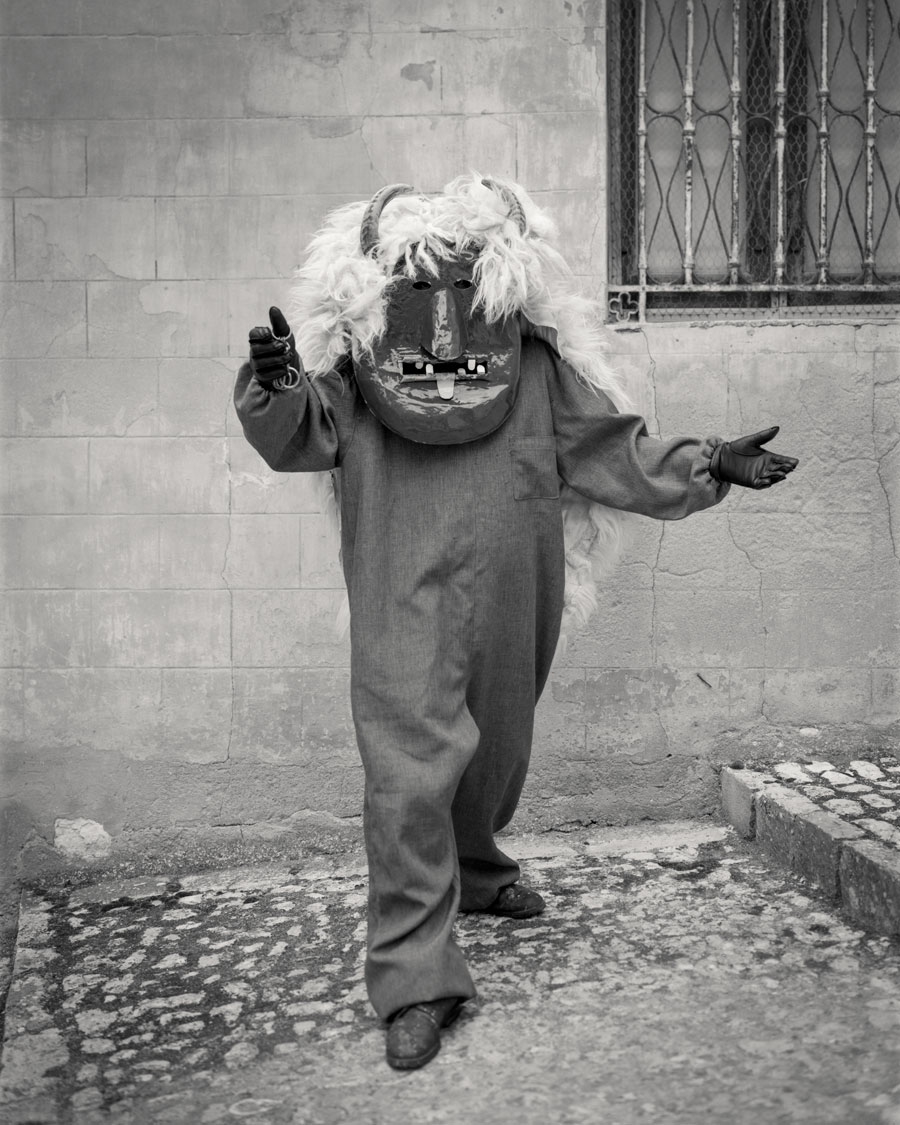

Shot entirely on large-format film, the project documents age-old rituals in the tiny communities that live rurally on the Italian islands of Sicily and Sardinia. The images show people in traditional garb, dressed as folkloric characters from old stories and fables. Set against the dramatic backdrop of a monochromatic landscape, the images are instantly compelling. There’s an immense sense of tradition and community in the photographs, and evident pride the people take in their craftsmanship.

Alys takes a considered, thorough approach to her documentary photography, and the results are richly rewarding. She is many things – a Taylor Wessing Portrait Prize winner, a Sony World Photographer of the Year winner, a Rencontres d’Arles shorlistee and was also a Wex ambassador. We were thrilled to be able to talk to her about her latest work…

Wex Photo Video: Thanks for speaking with us, Alys, and congratulations on the imminent publication of Gli Isolani. How did this project come about – how did it all start?

Alys Tomlinson: It started because I used to do a lot of travel photography – travel guides for places like Time Out. I got sent to Venice many years ago, probably about fifteen years ago now, and I had to do the whole guide. So I was roaming around Venice, and I had a big picture list to get, and on that list was a cemetery called ‘San Michele’, which is this very beautiful cemetery in the Venetian Lagoon.

It’s kind of set on its own, it’s very atmospheric, and you have to get the vaporetto [water bus] to even get to it. It was a very misty morning, atmospheric and evocative, and there were lots of Venetians travelling over on the vaporetto to lay flowers at the graves of their loved ones. It was just this really moving scene, and it had always stayed with me.

Initially, I thought of doing a project about mourning and loss, and basing it on the San Michele cemetery and I went there a couple of times. But obviously, it’s quite a complex subject matter to be dealing with, and I really had to question my motivation for that. In the end, I wasn’t really that comfortable with how I would progress it. So then – thinking about one of my previous projects, Ex-Voto, which was about religion and spirituality – I started looking into various festivals they hold in Venice, to celebrate certain days or Holy Week, these significant religious events.

Once I started researching that, I realised that although there was some of that happened around Venice in the north, a lot of those kinds of celebrations happened further south and west, particularly on the islands of Sicily and Sardinia. That's when I discovered these amazing costumes and masks that a lot of the locals wear as part of these festivities and celebrations. From there it took a different direction and ultimately ended up being about ritual, tradition, and identity for these Italian islanders.

WPV: So day-to-day, what was this shooting process like?

AT: Logistically this was a very different project from what I’d done before. When I did, for instance, Ex-Voto, it was a lot of me sitting around observing, waiting, being patient, looking, and making notes. And Gli Isolani is the first time I’d worked with what you would consider being, I suppose, a “fixer”.

She’s a great woman – an Italian woman named Giovanna Napoli, who’s actually a documentary film producer. She’s lived in Palermo in Sicily and has spent a lot of time in Sardinia, so she’s got a very good understanding culturally of these communities. But also, she is a wonderful mix of, I would say, persuasiveness and charm – obviously what you need to be a successful documentary producer – and I couldn't have done this project without her.

So, through my research, I gave her a list of communities and villages, and the celebrations and costumes I would ideally like to photograph, and then she went off and made an itinerary. We went to Venice two or three times, then Sicily, then Sardinia, and we would know exactly which village would be on which day. From there, we’d have a whole organised way of meeting the people we were going to photograph, doing a recce for the locations, and then setting up the photograph.

Initially, I was going to go with Giovanna during Holy Week, which is Easter, and is when many of these celebrations take place. But because of COVID, they’d all been cancelled for the last two or three years. Instead, we managed to go in between the breaks in the pandemic, when we were able to travel, and that meant we ended up setting up the portraits ourselves – people would wear these costumes especially for us, not for the celebrations.

It was a different way of working because it was constructed to an extent. But this also meant I had much more control over locations and backgrounds, and what landscapes I would use. Also, these festivals are often incredibly raucous and chaotic, so it would be very difficult to have any control over the situation to make portraits there. It allowed us to have much more control and allowed me to really have time to think about what I wanted to do with each person I was photographing.

The people we photographers were extremely excited to be wearing these costumes and masks again because they hadn't been able to wear them for so long. It became something of an event in the local villages.

WPV: So people didn’t take much persuading to be photographed?

AT: Not really. Most of them were very happy. They’re so proud of the idea of a photographer coming over from London especially to photograph them in these costumes and masks and to really try and understand these traditions.

WPV: You used a large-format film camera for this project, which is quite a cumbersome setup to lug around – not something someone would use unless they really want to. What is it that attracts you to that format?

AT: I’ve used the large format for the last few years on my two other big projects – Ex-Voto, and then a couple of years ago I did a project called Lost Summer about teenagers who’d had their proms cancelled due to the pandemic. I photographed them wearing the outfits they would have worn to prom, all in black and white in large format.

For me, it just makes me think in a completely different way. For my commercial jobs, I still use digital, because clients want a fast turnover of images, and they want to know exactly what they're getting. But for me, working with large format - it forces you to consider every shit. It makes you reflective and precise. It’s quite a meditative process – you go through things in your head, and there's a rhythm to the way you work. That’s partly because the film is so expensive, that I'm only taking a couple of shots per person, or per subject.

With Lost Summer, I was thinking about loss and longing. With this latest project, it’s more of a meditation on faith and spirituality and ritual. So large format has suited a lot of the subject matters I’ve chosen to focus on recently.

WPV: Can you take us through what was in your kit bag for the project?

AT: For a Gli Isolani shoot, I’ve got a Chamonix folding field camera. I only ever use one lens for everything, so whether I’m doing landscapes or portraits, I use a 150mm Schneider lens, and have a backup 150mm in my bag. I’ve got my plates, the film holders – slides I need to lug around that take two sheets of film at a time. I’ve got notebooks – I note down every single shot I take in terms of the aperture, the shutter speed, and the film, in case of any issues.

And then I’ve got some really exciting stuff – a bag of rubber bands! Also, I’ve taken to carrying around a small pair of pliers, because I’ve had incidents where my tripod broke mid-shoot. I’ve got a dust blower, a loupe (because I have to use a loupe with the large format camera), a light meter, and I have a big dark cloth to put over my head when I focus. I can’t use this camera without a tripod, so I’ve got a Manfrotto tripod and head.

WPV: Obviously you’ve done a fair few different projects, and I’d imagine you’ve taken something different from each one. Is there anything you feel you really learned or gained an appreciation for by working on this project?

AT: I think I hadn't really appreciated how deep these traditions run within these communities, and how often they are very central to the infrastructure of these villages. I was also quite surprised that a lot of the people under these masks are very young men – teenagers, or guys in their early twenties who lead ordinary lives. Some are bakers, a lot of them are farmers and shepherds, they’ve got all sorts of jobs. But they embody the characters when they put on these costumes.

There is a dichotomy in these communities. A lot of the young people are leaving for the big cities, because these are very rural lifestyles and employment opportunities are limited, but for the ones who are still there, their families are very essential to them. Their grandma will live around the corner, their aunt will be next door, and their brothers and sisters will have stayed in the village. It really made me appreciate the value of community, which is something it's not always easy to retain or identify, particularly in big cities.

Alys Tomlinson’s Gli Isolani is published by GOST Books and will be available from November 2022.

About the Author

Jon Stapley is a professional journalist with a wealth of experience in a number of photography titles including Amateur Photographer, Digital Camera World and What Digital Camera.