With hindsight, we should have expected film photography’s comeback. As photographers – and their audiences – grow tired of the fake perfection of heavily retouched (if technically outstanding) digital photography, a more authentic experience was always going to appeal.

Film is such a lovely medium to shoot in – rewarding for those times you take a bit of care, unforgiving when you don’t, and resistant to the life-savers of modern digital photography: you can forget about shooting 10fps to spare your sense of timing; and if your exposure isn’t correct to within a mere stop or so, all the editing software in the world won’t save you. There might be nothing more demoralising than muffing a frame of film – but there’s not much more rewarding than getting it right. Just the feeling of a proper, mechanical shutter and the pull of a winder gives us the shivers, which is why you’ll find everything you need to get started with film photography at Wex, from cameras, to film to darkroom chemicals and the scanners you’ll need to digitise your shots. And, now, the know-how to get started.

So start your journey here: how do you get started with film photography? How do you choose a film camera – and how do you avoid duds?

What’s the best film camera to buy?

So, you want a camera. You have some choices to make which will affect your entire journey through shooting film, starting with the format. The most obvious starting point is 35mm. Affordable, simple, and superb value for money. At the cheaper end of the spectrum, a roll of 35mm Ilford HP5 black and white film will set you back about six quid, give you 36 images to mess up and costs about a fiver to develop. Likewise, the cheapest roll of colour film you can get – presently Kodak Gold 200 – is about £6.65 a roll if you buy it in bulk, and costs about the same as black and white film to develop.

35mm film cameras are everywhere and will – if you’re patient – cost virtually nothing. My current go-to film camera is the 1984 Canon T70. It’s not much of a looker but it’ll do everything you could ask of a film camera. It’s a relatively sophisticated film camera, with both average and spot metering, a digital exposure counter, shutter priority mode plus full-manual exposure, and a handy-if-deafeningly-loud motorised winder, and it cost me all of £15.

You can spend much more, of course – aesthetes will want something along the lines of the Canon AE-1, a timeless piece of design with a manual winder that should cost between £80 and £120. The Canon AE-1 is hugely popular because of its classic styling, vast lens selection and incredible reputation for build quality.

Finally, you can opt for a point-n-shoot camera. These are enjoying a particularly spectacular resurgence, seemingly following Kendall Jenner toting a Contax T2. The appearance of Contax’s compact 35mm design on Jenner’s arm in 2018 prompted a five-fold increase in the cost of the cameras on the second-hand market. We told you film was fashionable.

Compact film cameras have many of the advantages of their digital brethren – you don’t need to worry about exposure modes or shutter speeds, focus or any of that malarkey. To which we say; where’s the fun in that? If you want to rock the same camera as Jenner buckle up – Contax’s go for about a grand. If you’re happy with something a little more basic, and conveniently, under £100 - the Olympus Mju should do the trick.

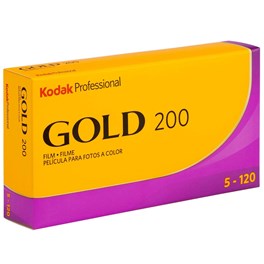

But wait! There’s more! 35mm is far from the only game in town. 120 film is absolutely everywhere – to such an extent, in fact, that 2022 saw Kodak release its popular, bargain-basement Gold series film in 120 format.

The differences? Where 35mm film has a frame width of 35mm (duh), 120 gives you frames in the order of twice as wide, around 56mm. The increase in film surface area gives you similar benefits to shooting a digital camera with a larger sensor – better resolution, finer grain (especially at higher resolutions) and improved image quality at large reproduction sizes.

That whimpering noise in the background? That’s your bank manager curled up in a ball because 120 film isn’t cheap. The cost of an actual roll is pretty reasonable – you’ll pay about a fiver for a 120 roll of Ilford HP5, or a tenner per roll of Kodak Gold 200 (albeit in a £49 five-pack).

Ilford HP5 Plus 35mm film (36 exposure)

High sharpness, fine grain, and exposure tolerance – these are some of the best qualities of the Ilford HP5 Plus 35mm film (36 exposure). This black and white medium speed film is focused on capturing scenes in good lighting conditions. Its ISO 150 makes the film suitable for capturing high-detailed subjects (indoor and outdoor). It can be over or underexposed without any disturbance in the final output.

£8.00 View

Kodak Professional GOLD 200 120 Film (5 Pack)

Kodak Professional GOLD 200 film is back! This medium format film is perfect for beginners and professionals alike working on a budget. As a daylight-balanced colour negative film, GOLD 200 offers a versatile combination of vivid colour saturation, fine grain, and high image sharpness. Available in a 5 roll multipack, this is the ideal affordable film for portraits, travel and everyday snapshots.

£49.00 View

The drawback is you get far fewer exposures: exactly how much 120 film is used per exposure depends on your camera. 645 cameras, such as the Fuji GA645i, shoot 120 film in 6x4.5cm slices and will give you around 15 exposures per roll. It’s all downhill from there – a 6x7 body like the Pentax 67 will shoot about 10 exposures, and a panoramic camera such as the Fuji GX617, which shoots 120 film in obscene, 6 x 17cm chunks, will net you just four exposures per roll.

120 cameras themselves run the gamut in terms of price. If you’re after something cheap and cheerful, Holga is still making new 120 cameras, and you’ll be able to bag a brand new Holga 120N right now.

If you’re after something with a bit more personality, 120 cameras come in all shapes and sizes. Feeling flush? How about something like the Hasselblad 500EL, which with a lens will set you back the thick end of a grand. Still less than a full-frame mirrorless camera, though…

The best features of a film camera

By the time film was replaced by digital, it was a thoroughly mature technology. So while you’ll never find a film camera with the bells and whistles of a current-gen digital camera, shop wisely and you’ll pick up something with plenty of features. Consumer 35mm cameras never got much better than the Canon 300X, for instance. Evaluative, partial and centre-weighted metering make getting accurate exposures easy, while the EF-mount means it’s compatible with an absolutely vast range of lenses, from mid-90s classics to brand-new L-series units. They lack the cool factor of more classic designs, but that makes them affordable – expect to spend under £50.

The older the camera you opt for, the steeper the learning curve. Did you know, for instance, that autofocus only made its début in the late 70s, and didn’t trickle down to consumer cameras until the late 80s? As you time-travel backwards other photographic niceties bite the dust. Through-the-lens metering – where your camera works out the correct exposure for you – simplifies once you reach the early 80s, but vanishes altogether halfway through the 70s, necessitating either an other-worldly sense for light, a light meter, or an app to do the job for you. If you want the full retro experience - a folding 120 camera, complete with crumpling bellows separating the lens from the body, will do the trick - but will be a fully-manual experience, from cocking the shutter to focusing and metering.

My suggestion? If you’re looking to get into film photography from a place of reasonable experience with digital cameras, a modern-ish film camera will fit the bill. Shoot for something from the mid-80s and you should get something with decent metering (if probably not autofocus), solid mechanicals and a good choice of lenses. The actual operation of the camera will be similar to using a digital body, and if you have some experience using a manual exposure meter, you should be off to a decent start.

Be warned though: film photography is a slippery slope, and this most definitely will not be the last spending you’ll be doing…

What issues can film cameras suffer from?

Sorry, I had to get over my laughing fit before I could answer this one.

Film cameras can suffer from almost every mechanical, electrical, biological (seriously) and chemical failure known to humanity. So, if you’re buying vintage camera gear, go in with your eyes open and your watchmakers’ screwdrivers at the ready.

If you’re just starting out – as I was a few years ago – you’ll probably be looking at film cameras not much older than the late 70s. The good news is that this was the era of real technological and mechanical mastery when it came to consumer electronics, and subsequently, there are lots of cameras out there with years of life left.

Of course, if you can see your prospective camera in person before you buy it - do! You’re dealing with a precision instrument - you need to see, hear and feel that the shutter and winder are crisp, and the exposure indicator – if there is one – dances eagerly around as you point the camera at bright and dark objects.

And apart from that… you’re sort of on your own. If you buy from a shop you’ll have some protection against your new camera being a dud - unless it’s sold-as-seen. But otherwise, you’ll have to wait until you’ve put a roll of film through it before you can be certain it’s working perfectly. Some cameras have shutters that slowly become inaccurate over time, so a 1/100th of a second might end up looking more like 1/60th.

Once that roll of film is developed you should look out for things like light leaks – where the film isn’t perfectly sealed from light while it’s in the camera, leading to entertaining but annoying splashes of colour and light across your frames. In some cases, light leaks can be repaired at home – depending on your level of mechanical confidence, available tools and willingness to potentially damage your new prize and joy. Otherwise, with such a glut of film cameras out there, there’s a huge community willing to lend its ideas and expertise if your camera behaves unexpectedly. You’ll also be able to find a decent number of spare parts for the most common brands. If self-repair is important to you, stick to the big names – Canon, Nikon, Pentax and Olympus all have plentiful spare parts and donor bodies available.

On the subject of damage. Since your new camera will probably mean new lenses – unless you opt for something with a Canon EF-mount, or a Nikon F-mount - so you should keep your eyes peeled for problems there, too. Since you’ll be using manual focus a lot more (perhaps exclusively), the focus ring on your camera should turn smoothly and freely – indeed since it was intended to be used every shot you’ll probably find it a more satisfying mechanism than the lens on your DSLR.

Be on the lookout for fungus as well. Fungus is caused by microscopic spores making their way into a lens, then sitting quietly in the dark and damp for years, which allows the fungus to grow on the inside of the glass elements in the lens. Fungus is tricky old stuff – it might not show up super well in online auction pictures, and depending on the lens you have it can be impossible to clean. The good news is – speaking from personal (bitter) experience, lenses can endure a surprising amount of fungus before it starts to obscure or soften an image – so don’t freak out about it too much. Plus, because lenses with fungus get such a bad rap, you can expect to save some money!

What else can we say? Have fun! From a personal perspective, shooting film was the beginning of a really joyful time for me in my photography – there’s less emphasis on capturing thousands of images, and much-reduced editing time, as well as the almost-endless satisfaction of getting an exposure just *so* in the camera.

Here are a few of my shots…

Shooting film? Make sure to tag us @WexTweets on Twitter or @WexPhotoVideo on Instagram so we can see what you’re up to!