How do you go about filming one of the world’s rarest animals? With the right kit and the help of Wex Rental, of course!

Hamish, one of Scotland's few remaining wildcats. All images © Wild Films Ltd

Dwindling in number, a sight so rare that lifelong Highlanders might never have caught more than a glimpse of one – the Scottish wildcats are a creature made all the more fascinating by their elusiveness.

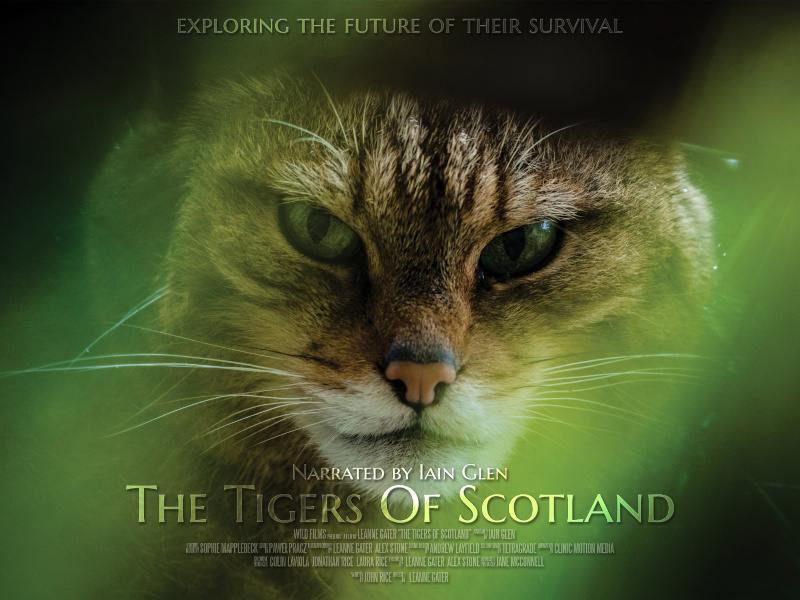

Filmmaker Leanne Gater certainly had her work cut out for her when she made the Scottish wildcat the subject of her first feature-length documentary, Tigers of Scotland, out now on Netflix and Amazon Prime.

The trailer for Tigers of Scotland

Beautifully shot, and starkly narrated in the grave tones of Scottish actor Iain Glen (perhaps best known for embodying Jorah Mormont on Game of Thrones), the film makes plain the stark reality of the wildcat’s plight. There are very, very few of them left. In fact, due to interbreeding with domestic and feral cats, there may well be no pure wildcats left at all.

Together with her partner, cinematographer Alex Stone, Leanne was faced with the task of not only tracking down the exceptionally reticent cats, but also capturing them on film. For that, she’d need the right kit, and Wex Rental were able to supply her with a few of the right tools for the job, including of course some seriously long lenses.

But what was it like, trekking into the heart of the Highlands to track down these fleeting felines? We wanted to know, so we sat down with Leanne to chat about the film and the shoot in a little more detail...

Wex Photo Video: Thanks for talking with us, Leanne. What’s a quick précis of the film Tigers of Scotland?

Leanne Gater: Well, the whole point of the film is to raise awareness for the wildcat. The wildcat has very complicated problems, and the film tries to go into a bit more depth with some of these problems. When I was shooting it, there were more than four-and-a-half thousand feral cats in Scotland, and at the time the working estimate was that there were around one hundred wildcats.

So there are just little things – like if you come across a feral cat colony, reporting it to cat conservation charities so they can be properly dealt with. Because, an important side of the film was also showing that a lot of the conservation to do with the wildcats is also all about looking after the feral cat population the right way, because they can pass across a lot of diseases and things like that.

WPV: Something the film makes clear is how few of the cats there are, and how shy they are. How do you go about approaching the challenge of trying to find them?

LG: Getting to know people on the ground is always a good start. One of the first things I would try to do was contact as many people involved in wildcat conservation as I could, and from there I tried to work out where I might find their habitats.

It was pure luck that we actually knew someone who lived up in the Highlands, and her family knew where there were stories of wildcats living, so that was a good place for us to start. We got to know some more of the people who lived around there, and we’d go around to see them – because you can’t sit in a hide all day, after a while you do have to get out because it does drive you a bit insane!

So we’d visit some of these other places where wildcats were known to be, and after a while we’d have locals ringing us up saying, “You just missed one by half an hour!” But that was really fascinating in itself, because you’d find there were certain routes the wildcats would regularly take.

For instance – there was one house where they knew all about the local wildcats; they even had names for them, and they’d take as many photos as they could. But the house that was literally next door to them had no idea there were wildcats there.

Islay, another of the Scottish wildcats

WPV: Because the cats were just taking incredibly precise routes – passing one house but not the other?

LG: Yes, exactly. They were just going through areas that they obviously preferred, but it was quite funny when the owner of the other house put two and two together – “So that’s where my chickens have been going!”

WPV: Let’s talk about the kit you hired for the shoot. I gather there were a few long tele lenses involved.

LG: Like most cats, Scottish wildcats have got very good hearing, very good eyesight, and a very good sense of smell. They know you’re around long before you know they’re around. So we knew from the start that we were going to need long lenses.

At first we started with a Canon 400mm f/2.8 L IS USM and a Canon 600mm f/4 L IS II USM, but we quickly realised that the 600mm was a bit of a hindrance. It was too long for the cats that we were working with in captivity, but it was also too big to take through some of the dense woodland that we were trying to get through. And so for most of the time, we ended up using a Canon 200mm f/1.8 and the 400mm, and we used those in conjunction with both a Sony FS7 and an A7S II.

WPV: Giving you a night-shooting solution as well with the A7S.

LG: Yes, exactly. Because the cats tend to be more active around dusk and dawn times, so a low-light solution was really key.

We had the A7s from my Wex Rental work anyway, and the FS7 was my own that I already owned. I was kind of the video person at the rental store in Manchester at the time; there was me and another person in the warehouse who knew pretty much everything there was to know about video at the time. I used to get a lot of questions about Sony in particular – everyone thought I was the Sony fangirl. Don’t get me wrong, I like Sony cameras, I do have a few, but I’ve actually recently just sold my FS7 and bought a Canon again.

WPV: Which one?

LG: The C500 Mark II. I think the interesting thing for us coming from the FS7 and going to a Canon was that Sony were kind of the revolutionary kings for quite a while, in terms of the Alpha series and the FS7. Canon were sitting on their laurels for a bit. But now I think the tables have turned quite a bit. It’s interesting from that perspective.

I mean, we just chose the kit that was right for us. That was the thing I always used to make sure of when I was talking to rental customers – it’s about the kit that’s right for you.

Leanne on location with lots of lovely long lenses

WPV: How long were you traipsing around Scotland for the shoot?

LG: The whole production period, from starting production to finishing editing, took about a year. Out of that, it was roughly seven weeks actually spent in Scotland.

Obviously that was mostly because we were trying to juggle it with work, there was only so much time I could get off. But also, you don’t realise until you embark on a project like this how expensive it is to support yourself while you’re doing it. Not necessarily just talking in terms of bills, but also food costs, and just getting up there. We were in very, very remote area, where you wouldn’t see another person for four miles. So that was a bit of an eye-opener in itself.

I learned a lot of what to do, and a lot of what not to do. We learned on the very, very first day: do not bring tinned food! It’s so heavy, trying to trek it for miles.

WPV: How many of you were on the crew?

LG: It was just me and my partner at the time, who’s now my husband. We were the shooting crew, and then it was on the post crew I brought in an editor, an animator, a composer, a colourist, a sound designer and a writer. I’m a competent editor, but I didn’t wanna tackle doing my own hour-long film. I thought that’d be too much – I was already stressed enough.

WPV: So is this your first film approaching feature-length?

LG: Yes. It’s my first major film, as it were; I’d done a few short documentaries beforehand, and this idea did start out as a short film. But I quickly realised when I started researching it that it was just too complex to cover in a short film.

WPV: It’s a really interesting subject – it feels like a lot of people are starting at a level of complete ignorance, where they either straight up don’t know that Scottish wildcats existed, or they know Scottish wildcats existed and that’s the only thing they know.

LG: There are so many people that have come up to us in person,or said over Facebook or email or whatever, “Wow we didn’t even know these cats existed.” And, well, that’s kind of the point.

I knew that they existed beforehand, but I had no idea until I started researching that there were so many problems. It started from a previous visit to Scotland; we went into a wildlife hide, and we’d just got chatting with the host, and he said as someone who had lived and grown up in the Highlands all of his life, he’d only ever seen three wildcats. And they were all such blink-of-the-eye moments.

In the Highlands, it’s kind of this revered creature. It’s the subject of a lot of folklore – cats feature in a lot of clans’ mottos and on their crests, and that folklore has made its way through into some of the whisky houses as well. Clynelish, for example, have a wildcat on their bottle.

So the folklore is there, but that doesn’t seem to have come out from the Highlands – go into the houses there, and you’re back to people being like they are in England, saying things like, “Well, I didn’t know these cats existed!” But you’re Scottish! You should know! It’s practically your national creature!

WPV: It’s a great subject for a film like this – even if it’s a challenging one.

LG: It was difficult to find them, but it was also difficult in the initial stages to get people’s trust. Part of the problem was that I was just an unknown; people didn’t have a clue what my intentions were with the film, even though I’d sent them this big document trying to lay it out as much as possible. I’ve since learned that that’s not the best way of doing it, because people don’t want to read what is effectively an essay.

But at the time i thought that was the best way of getting through to them, so I could say, “Look this isn’t about taking sides with anybody, this isn’t about finding them so people can go and shoot them or anything daft like that.” And it just took one site agreeing to give us a chance for the others to pay attention.

WPV: Do you have a next project in mind?

LG: I have several that I’ve been working on since I finished Tigers. A documentary is a long old process. I was chatting to one of the heads of Ammonite film productions in Bristol, and they said one of their projects took twenty years to get off the ground! So it does take a while.

There’s one that I’ve been over to America to shoot a trailer for. I was hoping to have gone back this year, but obviously the pandemic happened. I’ve also been working on another one, which I was quite interested in getting off the ground. There are always ideas. It’s just about getting those ideas out in the ether.

WPV: Has bringing this film to a close been a confidence-booster in that regard?

LG: It has and it hasn’t. Because I feel like now that I know about the wildcats, they’ve almost got their claws in me, and it’s hard to shake them off. A lot of my initial ideas involved going back to do some more work with the conservationists, but sadly they didn’t pay off. It wasn’t something that we could afford to just go and do like we did with Tigers – we kind of ran our money reserves dry!

There is some exciting stuff going on at the moment with the wildcats, so perhaps in the next couple of years I’ll be in a better position to be able to carry on the story. A lot has changed since the film was made – one of the main organisations we worked with was Scottish Wildcat Action, which was a government body set up for a certain amount of time. They only had five years for an action plan to see what they could do to change the fortunes of the wildcats, and that unfortunately ended in March of this year. It’s all now being passed on to a new group called Saving Wildcats, but one of the key things they realised during the action plan was that there’s just too few cats out there.

I think it was at the beginning of last year that they were actually declared functionally extinct in the wild. When we were shooting, our rough estimate we were working to was about 100 cats in the wild, and then that was quickly revised down again to about thirty. Which is why they’ve been declared functionally extinct – because there’s just too few of them. You can’t support a species on that few. So it’s all shifted now towards captive breeding and reintroducing the cats as soon as they have enough of them and a place to do it. Last time I spoke with them they were working with the guys who were some of the masterminds behind the reintroduction of the Iberian lynx – so there’s a sort of model to work with.

WPV: That’s definitely a story. I hope you get to do something on it.

LG: I’d love to. It’s just about bringing everything together, isn’t it?

Leanne Gater was talking to Jon Stapley. The film Tigers of Scotland is available to watch now on Netflix and Amazon Prime. See tigersofscotland.com for more.