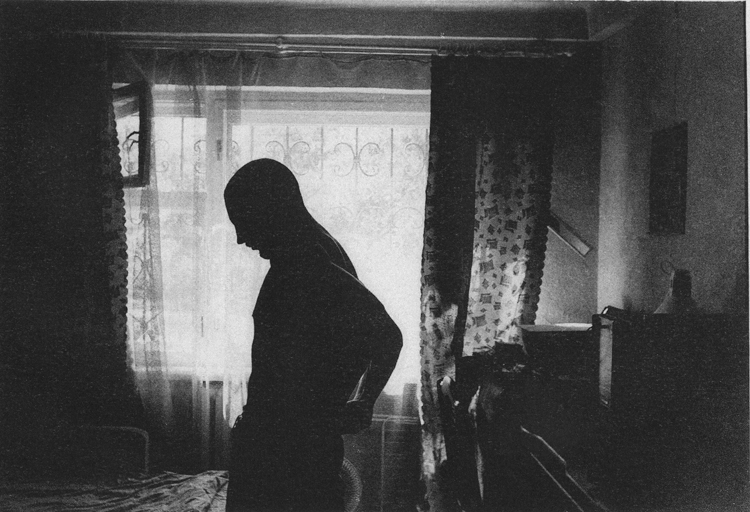

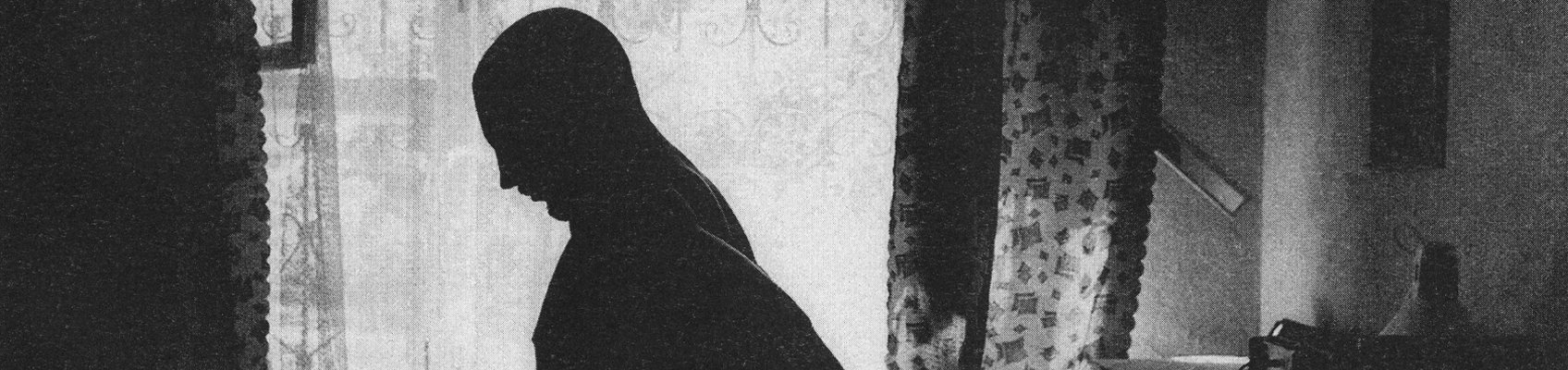

The images on this page depict men who are fighting wars on two fronts. On the one hand, they are Ukrainian servicemen fighting against Russia’s full-scale invasion of their country, braving drones and bombs and bullets to defend their homes. At the same time, as some of the few openly gay men in the Ukrainian armed forces, they are also fighting for acceptance, and to be seen.

Their story was beautifully told in The Face magazine at the tail end of 2024, in a long read written by Serhiy Morgunov, produced by Eugenia Skvarska and photographed by Jesse Glazzard. Now, Glazzard’s beautiful analogue images from the series, taken from a whirlwind nine-day stint in Ukraine, are being exhibited as part of Photo London.

Glazzard, who hails from West Yorkshire, is a veteran portrait photographer with a long list of prestigious clients and subjects across his portfolio. He has photographed popstar Christine and the Queens and shot the cover of British Vogue, but going to a warzone was an entirely new experience — challenging, exhilarating, at times heartbreaking.

We were thrilled when Jesse agreed to tell us more about his experience of shooting this singular story. Read on for our conversation with Jesse, which has been edited for length and clarity.

You can see more of Jesse’s work at jesseglazzard.com.

Jon Stapley: Thank you for speaking with us, Jesse. How did you first come to be involved with the Ukraine project?

Jesse Glazzard: So, Eugenia Skvarska [the project’s creative producer] was on the Central Saint Martins Master’s course two years after me, and Adam Murray who ran the course said, “You guys really need to work together.” And I think that just stuck with Eugenia, and then she found the LGBT military in Ukraine and asked me, “Do you want to do it?”

I didn’t even think about it. I felt I needed to get out of my comfort zone. So I just went, which was kind of naive, but I think in a sense the naivety was good, because I don’t think I would have gone if I’d known there would be bombs over my head.

JS: How did things play out from there?

JG: When I arrived, I’d been travelling for two days, and Eugenia called me and said, “Get in the underground, there’s a bombing.” They were disarming bombs in the sky. It was terrifying. The train station shook and people were crying and I was just like, “What am I doing here? I’m going to die.”

That day, I said to Eugenia that I was going home. She said, “But you made it all this way, you have to stay. You have to do it for history.” When she said that, I thought, “Okay. Fine. I’ve got to stay.” I was there for nine days, shooting two to three soldiers per day, going to their houses and estates.

JS: I think that’s interesting, because the portraits have a feel of closeness and intimacy to them — they feel like the kinds of portraits where a photographer has spent a lot of time with their subject, but obviously you didn’t. Did you have to build up trust and rapport quite quickly?

JG: We’d spend an hour chatting. If they couldn’t speak English, Eugenia would translate. I was listening mostly rather than talking — I spent a lot of time listening to their stories, and there were moments where I just really wanted to cry. One guy we shot, he went to war at 18. It was heartbreaking to hear that story.

I think they just wanted someone to listen. And they wanted to be photographed, they wanted to be documented and to tell their story. So I think there was a mutual trust — they seemed to trust me. I guess if someone’s travelled for two days and is risking their life, you’ve got to trust that photographer! I was just so grateful they were open to sharing their stories with me.

JS: The stories are so affecting just to read, so I can’t imagine what it would have been like to hear them in person, even through a translator. Were there any stories in particular that affected you or really stayed with you?

JG: The guy that has the scar from the bullet wound. I remember when he took his pants off to show us, my heart fell through all of the apartments. I almost felt like I shouldn’t have been taking the photo — I really questioned whether I should have been doing it. HIs eyes were so kind, and it was just heartbreaking that he’d experienced that, and he couldn’t walk so well.

I think also Vlad, who fell in love on the frontline. They’d been together for about six months, and then he had to pull his partner out of the trenches. But he and every single person were also so kind. It was heartbreaking to see that you can go through so much, and still be an amazing person.

JS: Something that struck me with Vlad’s story, and with another soldier featured in the piece called Oleh, is that they both talk separately about experiencing a moment where they fully believe they are about to die, and their last thought is to come out — that they want to come out as gay. Is that partly why it felt important to document queer soldiers specifically, so that their identity doesn’t get lost in the horror of what’s going on — because it clearly still matters to them.

JG: I think that was what was important to Eugenia. And for them [the soldiers], it felt really important that identity was a huge part of this project, and them speaking out. But for me, that was the last part of this story. At the end of the day, these people are just humans, and they’re fighting for their land. They’re good people. It’s very risky for them to come out in this way.

JS: Was your approach in Ukraine different to your normal approach for shooting portraiture? Or the same?

JG: I try to photograph everyone like they’re a friend. I’m trying to build a relationship with someone, so the photos can be the last element. I could spend two hours getting to know someone, and then it’s fifteen minutes of shooting. I don’t know if I would be a good photographer if I didn’t have a connection with the subject. Some people can do that, but I just can’t — I think it’s a very emotional thing for me. It’s my language. How I express myself is through photography. So if I don’t have that connection, I’m not able to access their language and my language.

JS: The images really are beautiful. They’re shot on film?

JG: Everything’s analogue. And now we’ve risographed everything.

It’s just my medium. I’m not that interested in digital, I’ve never been that interested in it. I like the slower process of analogue and being in the darkroom. Because you create these connections with people, and that’s great, but then you also need time to rest and then you can go and be with the work.

About the Author

Jon Stapley is a London-based freelance writer and journalist who covers photography, art and technology. When not writing about cameras, Jon is a keen photographer who captures the world using his Olympus XA2. His creativity extends to works of fiction and other creative writing, all of which can be found on his website www.jonstapley.com

The Wex Blog

Sign up for our newsletter today!

- Subscribe for exclusive discounts and special offers

- Receive our monthly content roundups

- Get the latest news and know-how from our experts