Emil Lombardo loves to tell stories. Born in Argentina, and since moving to Paris and London, he has been shaping his documentary photography by focusing his lens on people who are pushed to the margins, whether for reasons of gender, sexuality, immigration status, poverty or any other aspect of their identity.

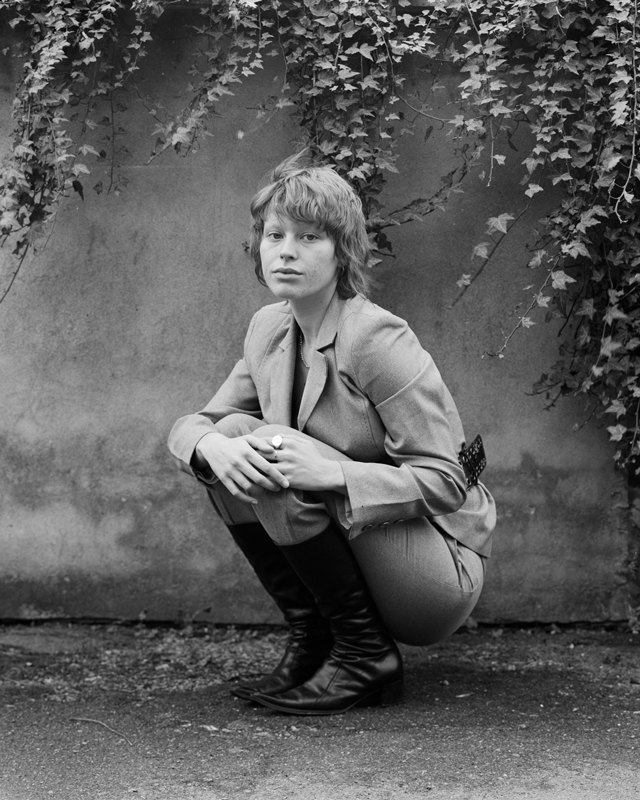

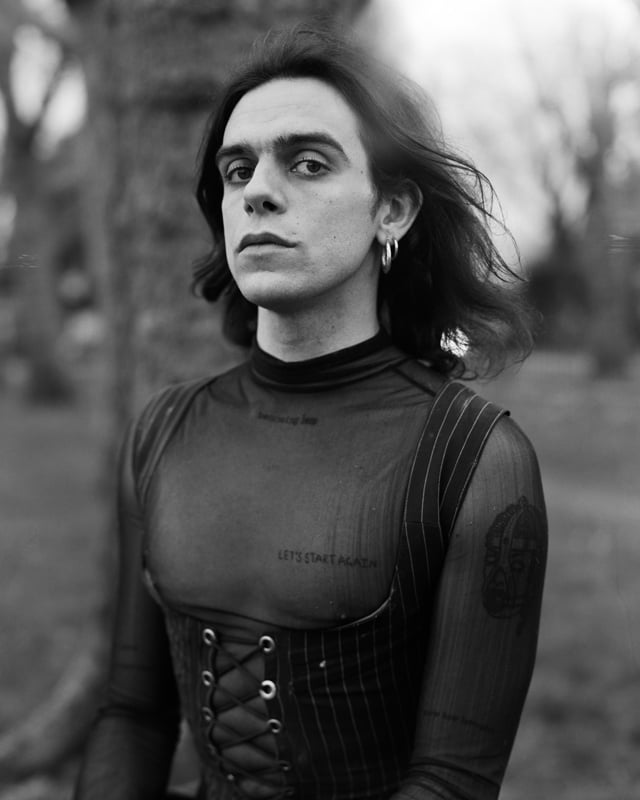

Emil’s career has already encompassed many different projects. His first major work, Political Existences, was a global collection of street portraits created in collaboration with LGBTQ+ charity Spectra for Trans Day of Visibility 2020. When the exhibition was postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Emil instead displayed the portraits publicly across the streets of East London. In the ensuing lockdowns, he cycled across the city for a project that became known as “An Unending Sunday Morning”, photographing trans and non-binary people outside their homes as a documentation of the strange, fluid time everyone had found themselves in. More recently, he has photographed the vendors of the mutual aid publication Dope Magazine.

It was a pleasure to sit down with Emil and dig into his career and his work. Read on for our conversation, which has been edited for length and clarity.

Jon Stapley: Thank you for speaking with us, Emil. How did photography start as an interest for you?

Emil Lombardo: It was 2008. I started photography when I was doing my master's in computer science. Growing up, I’d always been creative. I used to play music, I used to write poetry — I had a creative side. I chose computer science for a purely pragmatic reason. I had quite a poor background in Argentina, and I couldn’t give myself the privilege of doing what I wanted to do. So I studied science, but it was never something that I actually enjoyed.

I bought my first camera, and I just really fell in love from there. My first camera was a digital camera, and quite quickly, I switched to film. I think I was spending so much time with computers in my daily life, I wanted to go as analogue as possible. I didn't want to do anything with pixels.

I taught myself at the beginning. I experimented and I learned. I played with alternative processing, like cyanotypes. I built my own lighting, I had my own studio. I was taking portraits of friends, lovers, family – landscape, architecture, whatever. For a long time, it was a hobby that I was passionate about, but I couldn't possibly think about quitting everything and going for photography. I was scared of that.

When I moved to London in 2016, I was going through another very bad moment after a breakup. I started some evening courses in Central Saint Martins, because they were darkroom courses. The darkroom is a very meditative place to be, especially when you have too much in your head.

I spent a lot of time in the darkroom. I decided, maybe I could do something more serious with photography, which I had always dreamed of. I decided to apply for a master’s at the Royal College of Art. From there I really realised my practice, evolving in a more serious way.

JS: In 2020, you were going to do the Political Existences exhibition, but that was cancelled by the pandemic, and you ended up putting the images on the streets of East London. Why did it feel important for them to publicly show it on the street in that way?

EL: That project, it was about the street. I chose this protocol of everyone being in the middle of the street, because of all the connotations that the street has in terms of visibility, some of which are super obvious, and some maybe are less obvious. In terms of who gets to be on the street, who is safe in the street.

I was very excited, because it was my first serious show. It felt like I was taking the subjects and showing them in a more holistic way. Not everyone would go to a gallery, so I thought maybe it was better to go back to the street. I wanted other people to see it.

JS: With regard to portraiture, how do you approach the non-photographic aspects of it? Like getting to know someone — do you feel you have to get to know someone to take their portrait?

EL: No.

JS: That’s so interesting. Because I’ve heard photographers say the exact opposite — that they literally can’t photograph someone if they don’t feel they know them. And I guess some must fall more in the middle.

EL: I’ve realised that I photograph better people that I don't know. I feel I don't photograph my friends or family or lovers well; I don’t do them justice. I feel like I'm never happy when I look at the pictures that I take of people that I’m close to. Somehow, I prefer not knowing.

When I was shooting the following project, during the lockdown, I made a call-out on social media, looking for people to photograph outside their homes. Some people would email me and say something like, “Oh, I'm interested. This is me, if you want to have a look, this is my Instagram.” And I wouldn't click on it. I didn't want to know what they looked like, because it makes you project something.

JS: For that lockdown project, you cycled all over London to photograph people. What was that experience like? It must have been surreal.

EL: Yes, but it was actually so nice as well. I believe that there are positives and negatives in everything. It's part of my faith — I’m a buddhist. I see everything as very interconnected. The lockdown, and COVID, was a really weird and very sad moment, but I was able to experience a lot of joy in many other things.

It was hard, especially the second lockdown in London, which was more depressive for people. It was winter. People were more scared. There was the Delta variant. It wasn't like the first one, where it was Spring. But I remember that I always felt a lot of joy, cycling around London. It was super-empty, and I love cycling. I have these memories of having whole big avenues to myself. And it was really, really nice. Even if it was really cold!

JS: Meeting so many different trans and non-binary people must have been a useful way to kind of explore LGBTQ+ identities in an intersectional way, which I know is important to you. You were able to meet people of different classes, people of different immigration status. This might be a bit of a basic question, but why do you think it's important to explore stories with that intersectional lens, looking at different aspects of people's identity?

EL: I don't see things as separate. To me, it doesn't make any sense just to talk about trans identity, because no one is just “trans”, like how no one is just black. As humans, we live in this beautiful world with billions of people on it, and we have billions of stories, and each one is different.

When it comes to identity struggles, we all have different struggles, and it's really important to highlight those experiences, because we still don't have enough of it. Anti-progressive people tend to think that we’re only talking about this. I don't think so. I think we still have all the other narratives going on, in the media and in the press, in television, and also in the art world, and photography.

This is just my opinion, but the way I hope I can contribute is that we need to tell these stories with enough care, enough empathy, to show the reality, but without stigmatising anyone, or without focusing on the most negative parts. Even though those parts are there, and it's important to talk about them — what I hope, always, is that I can show how people are, without having a sort of voyeuristic perspective.

JS: I know you also use your practice to explore aspects of your own identity, with regard to gender and sexuality. How do you feel that photography has reflected, or maybe even helped your own identity journey?

EL: I think there are different aspects to that. First, this is always a topic that interests me because I live it — it's something that I live, as a trans person, as an immigrant, as someone from quite a poor background, I had social mobility in my life; I ended up here. But I still have family there, and we very much still live with those problems.

Those are things that I feel I have a certain legitimacy to talk about. But I’ve also learned a lot from it. I have progressed a lot through my own journey, through photographing people. When I photographed the first project you mentioned, Political Existences, I was way earlier on my journey with gender. I wasn't even out completely to many people. I had not even medically transitioned.

Through doing that project for several months, photographing different people, I heard so many different interesting stories. I became friends with many of the people that I had photographed. They shared their journey. And after a while, things start making sense in my head — I’m thinking, “Why is it that I haven’t addressed these things in my life? Why haven’t I reflected about this?” There's actually a self-portrait in that series, because I wanted to be part of it. That's a portrait I took right at the end.

There’s a project that I've been doing for a while now, with a magazine in London. It's about inequality and poverty, something that’s becoming very important at the moment. And I'm actually reflecting back to things that I didn't address from my childhood.

JS: Can you tell us more about that project?

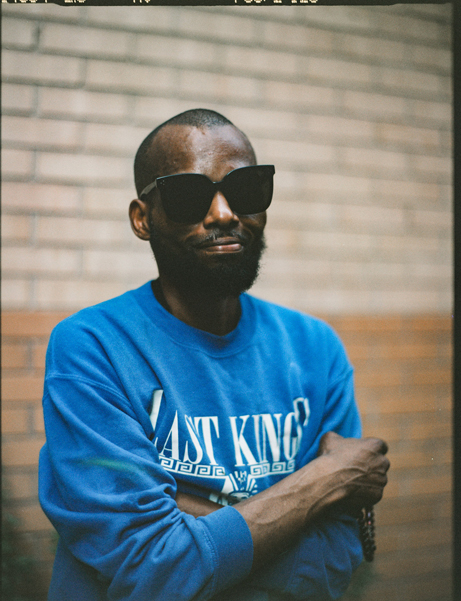

EL: It’s this magazine called Dope magazine, and it's distributed in the street by people who have financial struggles. It’s not only homeless people, but anyone who feels like they need some solidity, they sell the magazine and they keep their revenues.

They’ve started doing interviews with the vendors and I’ve been doing portraits of them. It’s a great project — it’s very different from the others. There are many different types of stories, and different kinds of people. The interviews are done by the editor of the magazine. I'm not really present during the interview, because I leave them time to chat. I always discover the interview later, once I’ve already printed. And their stories are so human, so honest.

I think there's way more stigma with poverty, especially with people who live in the street. It's almost like no one wants to even look at them, or address them, or talk. I think it's insane that we live in a world where we have people living in the street, with all the resources that we have. And for me, I know that this is something that in photography, we haven't always portrayed in a good way. There's this term — “p*rn of poverty”. In my head it’s like, I want to take these pictures as far away from this as possible. I don't want people to just look at those pictures and think, “Oh, this is a homeless person.”

It might be my way of feeling, and I know maybe some people won't share this view, but I don't like when photography is used for pity, or instrumentalising someone to generate sadness in the person who’s looking at it.

JS: Looking into the future, do you have any particular ambitions? Is there anything you’d really like to do that you haven’t done yet?

EL: A big dream of mine is to go to Syria, because I have family from there. It was a dream of mine even before photography. When I graduated, many years ago, I had a plan to go, and then the war started just after. If I ever go, I will try to do something — I have images in my head, maybe even with my family. It's a big dream of mine. I hope I will go one day.

You can see more of Emil’s work at emil-lombardo.com.

About the Author

Jon Stapley is a London-based freelance writer and journalist who covers photography, art and technology. When not writing about cameras, Jon is a keen photographer who captures the world using his Olympus XA2. His creativity extends to works of fiction and other creative writing, all of which can be found on his website www.jonstapley.com

The Wex Blog

Sign up for our newsletter today!

- Subscribe for exclusive discounts and special offers

- Receive our monthly content roundups

- Get the latest news and know-how from our experts