If the answer is yes, that boredom is both the point and the indictment – not of Goldin’s work, but of us. In a present saturated by livestreamed death, by bodies endlessly violated then flattened into content, shock has been strip-mined of its power. We scroll past what once would have stopped us cold.

There is a particular cruelty in looking at Nan Goldin’s photographs today. Not because the shock has softened with time, nor because the discourse around her work has grown tired, but because so many now resist what her images insist upon remembering: that barely three decades ago, the world burned itself alive with desire – and that it was recorded by a woman who refused to soften the aftermath.

And that, even now, we still cannot bear to look.

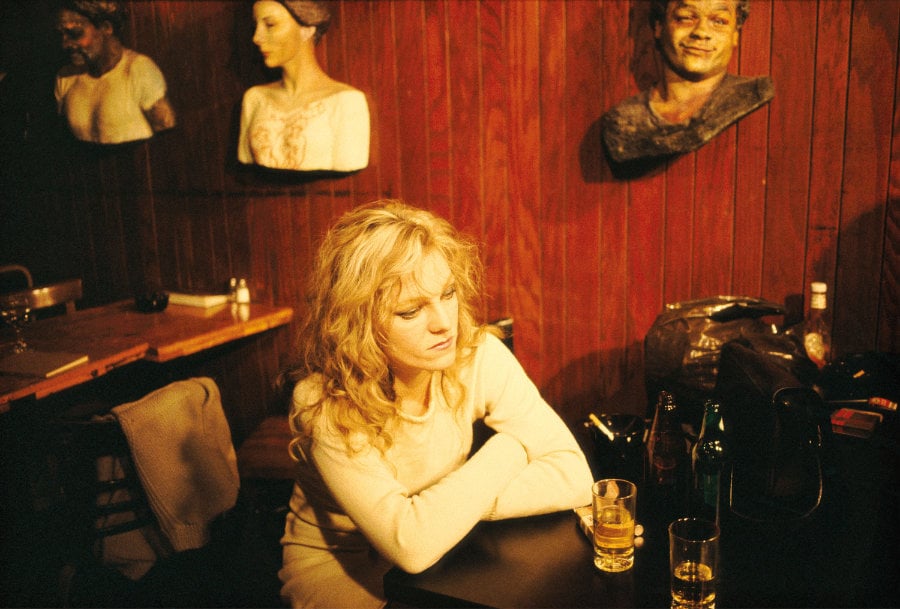

Goldin’s work has long been exiled to the edges of what is politely termed transgression: sex and substances, queer bodies, domestic brutality, addiction rendered intimate. Yet to catalogue the work this way is to diminish its radicalism. These photographs were not provocations; first, they were testimonies. They were, and are, documents of attachment, of what happens when love, dependency and identity collapse into one another, becoming heart-wrenchingly co-dependent and catastrophically, irrevocably life-altering.

As Goldin’s work makes its gallerific rounds once more, showing at London’s Gagosian from January to March 2026, intimacy offers no refuge. It is unstable, incandescent, and frequently fatal. Desire does not redeem; it devours. Affection curdles into affliction. Beauty arrives already bruised. And yet, within this volatility lives a devastating tenderness – the kind that insists on being felt, even as it threatens to undo those who cling to it too tightly.

For those that have lived under a metaphoric rock, The Ballad of Sexual Dependency constructs something closer to a philosophical document than a photographic series. Borrowing its title from Bertolt Brecht, the work unfolds as a visual argument about love under capitalism; about bodies consumed by one another in the absence of structural care. Lovers cling. Friends disappear. Pleasure and self-destruction collapse into the same breath. This is not romance; it is survival staged as a fever dream fuelled by cocaine-charged, sleepless and seething nights. It plays out in bedrooms, bathrooms and basements across underground downtown New York, where intimacy hits harder than the drugs, and morning is never guaranteed.

The shock factor – naked bodies, split lips, needles, smeared makeup – is not provocation for its own sake. It is epistemological violence. Nan insists that truth resides precisely where polite society edits, erases and averts its gaze. That insistence feels even more urgent now. We live in an age where violence is branded, where conflict is marketed as courage, where war is aestheticized and suffering reframed as spectacle.

Shock has become so obscene, so incessant, that we have effectively lost it. And yet Goldin’s images still wound. They still unsettle. They still ask a question our present moment desperately avoids: what does freedom look like when the body is the final asset, and the self is both currency and collateral?

Vanity, in Goldin’s world, is armour. Drag queens, lovers, addicts, artists perform themselves relentlessly – for coherence, rather than applause. Identity is assembled nightly, often chemically, beneath flickering lights and collapsing ceilings. Performance becomes preservation. Exposure becomes survival.

What makes the work truly devastating is Goldin’s refusal to pretend she was ever separate from it. She is not merely an observer; she is implicated. The camera indicts her. When she photographs herself after being beaten by her partner, the image shatters any lingering comfort. To look away would be a second act of violence.

The heartbreak compounds with time. Many of the faces staring back at us did not survive the decade: lost to AIDS, overdoses, suicides. The images quietly catalogue absence before absence fully arrives. In this sense, Goldin’s work functions as an archive of pre-grief. The photographs do not mourn in retrospect; they tremble with loss in advance.

And yet, for all its darkness, the work resists nihilism. There is care here. There is the stubborn, almost defiant belief that being seen – fully, unsafely, without correction – still matters.

In an era dominated by curated vulnerability and algorithmic confession, Goldin’s photographs feel almost unbearably sincere, and disturbingly contemporary. They demand your presence and attention more than your admiration.

To engage with Nan Goldin’s work is to accept that intimacy can injure, that desire can hollow us out, and that love does not guarantee survival. But it also reminds us that to live, truly live, is to risk tenderness in a culture that no longer recoils from death, that commodifies bodies and rehearses violence until it feels inevitable.

That is the tragedy. And that is why these images remain some of the greatest ever made.

Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, is running at London’s Gagosian on Davies Street, January 13–March 21, 2026.

About the Author

Tiffany Tangen is Head of Content at Wex Photo Video.

The Wex Blog

Sign up for our newsletter today!

- Subscribe for exclusive discounts and special offers

- Receive our monthly content roundups

- Get the latest news and know-how from our experts