Many years ago, I was a bit cautious about entering the world of macro photography. At the time, I was focusing all of my attention on larger mammals and birds, and I realised that I needed different camera gear to start photographing the smaller things. I was tentative about investing money into a new lens, different tripod head and all the bits of gear that are associated with this genre of photography.

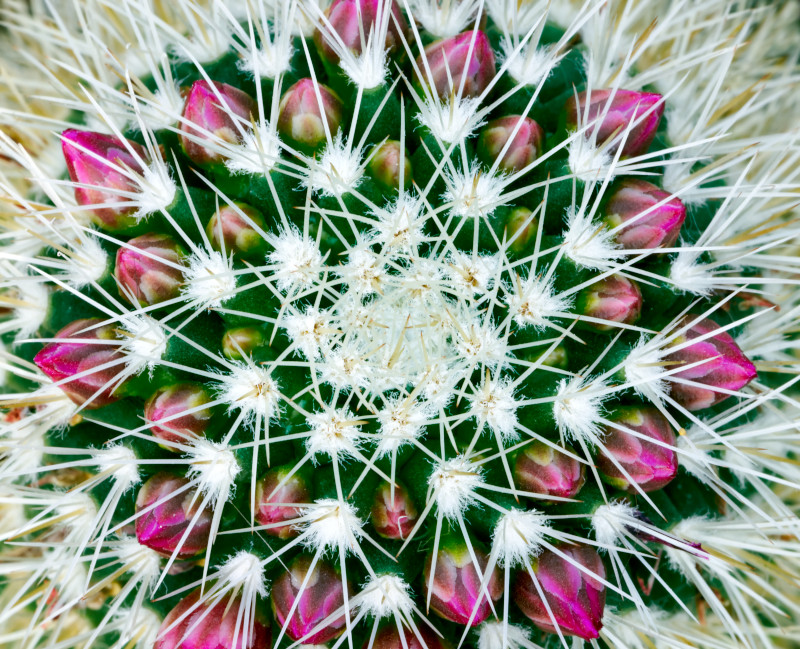

But I tentatively put my toe in the water, buying a 180mm macro telephoto, a ring flash and a Kirk ball head for my Gitzo tripod, endlessly chasing bees around the garden before realising that flowers, and indeed my household cactus represented a better (and easier) place to start. I saw fascinating details that my human eye couldn’t see. And I was hooked!

The early years! Practicing with the 180mm macro on the household cactus in 2009. Canon EOS 5D Mark II, Canon EF 180mm f/3.5L Macro USM, tripod

Since this epiphany, I’ve added small items to my macro kit list, like reflectors, a cable release and LED lights. Over the years, I’ve approached macro photography slightly differently by also using gear that I would normally reserve for my photography of mammals and birds.

I still very much focus on mammal and bird photography. However, macro adds a whole new dimension to one’s capabilities and expertise as a wildlife photographer.

What is macro photography?

Macro photography can have slightly different definitions depending on who you ask. The precise definition is an image where the subject is reproduced to at least 1:1, meaning the image on your camera sensor is at least the same size the subject itself, or even larger. So, in effect, it’s a way that you can make a small subject look big, showing intricate details that we can’t see with our eyes.

What lens is best for macro photography?

Taken at dawn with dew on the vegetation, using a 180mm telephoto macro lens. The early morning light added a cooler, blue mood to this image of a roosting blue butterfly. A tripod added stability for the early morning shoot. Canon EOS 1D-X, Canon EF 180mm f/3.5L Macro USM, tripod

Macro lenses tend to be more specialist with a higher price tag, essentially because fewer of them are manufactured. The optics of a macro lens are designed specifically for close-up photography, meaning that you can focus much closer to your subject than a conventional lens. Most macro lenses will produce a 1:1 picture of the subject at their minimum focusing distance, and some will have even higher magnifications than this (Canon’s original MP-E65mm for example, has a 5x magnification).

My preference is a telephoto macro lens, either a 100mm or a 180mm. Not only does this type of lens have a very close focusing distance, the telephoto aspect helps to isolate the subject and create a lovely bokeh at wide apertures.

Can you use a macro lens for normal photography?

Using a wide aperture with a macro telephoto lens creates ‘mush’ or bokeh, making the subject stand out. This Balkan terrapin was photographed in its habitat on the bank of a pond. Lying on the ground to take the shot put me at eye level with the terrapin, creating a connection between the viewer and the subject. Canon EOS 1D-X, Canon EF 180mm f/3.5L Macro USM, beanbag

In short, yes you can. As with many things, there are pros and cons to using a macro lens versus an alternative lens with the same focal distance.

Macro lenses can be used for other photography, portraiture for example, because of their ability to focus at close distances and their incredible detail and sharpness. They can, however, be slower and less accurate in terms of autofocus (so not ideal for fast movement), and they tend to be a stop lower, so ‘darker’. And believe it or not, they can actually be ‘too’ sharp, showing too much detail in an image.

So, given the specially designed optics, and image sharpness and detail of macro lenses, their low f-stops and minimum distance focusing, I prefer to reserve macro lenses for my macro work, manually focusing on my subjects and creating some nice bokeh.

How to do macro photography without a macro lens

A silhouette of the praying mantis, taken in woodland using sunlight filtered by the tree canopy. The 100-400mm zoom with its capacity for close focusing was an ideal lens for this shot. Canon EOS 1D-X, Canon EF 100-400mm f/4.5-5.6L IS II USM, handheld

Macro photography is possible without a macro lens. Some of the newer lenses now have impressive abilities to focus at close distances. I’m a big fan of Canon’s 100-400mm II with a minimum focusing distance of 0.98m.

Additionally, I will often use a 300mm prime lens for macro photography, where I want to show my subject in its habitat – an approach that works very well with many wildlife subjects.

A non-macro telephoto like the 300mm prime lens is great for habitat shots as seen with this Copper butterfly. Manually focusing on the butterfly using a wide aperture creates a lovely bokeh. Canon EOS 1D-X, Canon EF 300mm f/2.8L IS II USM, handheld

Don’t forget that you can try using a wide-angle lens too, like a 24-70mm – an approach that is often overlooked and a great way to show a small subject in its environment.

I would also suggest experimenting with extension tubes, also known as extension rings – these devices fit between the lens and the camera. When attached to a lens, they basically increase magnification and reduce the minimum focusing distance by moving the lens further away from the camera sensor. Because the tubes have no optical element, they do not affect the quality of the lens, but they do decrease the light and provide a shallower depth of field. In effect, the longer the extension tube, the closer the lens can focus.

Using a range of lenses for your macro work will help you to build a strong portfolio of one subject, ranging from close-up details, to habitat shots. It stetches the traditional definition of what macro photography is, into the realm of photographing the ‘smaller things’ with a number of creative approaches.

How to build a macro photography studio

Macro photography in your own homemade studio can be rewarding. You’re in control of everything – the lighting, backgrounds and foregrounds, camera positions, and the environment is calm meaning there is no breeze moving your subject!

The particulars of building your own macro studio very much depends on what you wish to photograph. I would recommend this approach at home if you are photographing inanimate subjects. It’s very easy to set up a macro studio on a table in your home and it doesn’t take up much space.

Try using some white paper or card bent against a wall to form a curve. Alternatively, if you don’t want a white background or foreground, you can change the colour of the card to alter the mood of the images.

Another creative approach I like a lot with my own pop-up studio is using glass and acrylic; these substrates create incredible reflections and are very effective for some subjects. One word of advice when using highly reflective surfaces – diligently wipe them with an anti-static cloth before each shoot in order to remove dust particles, otherwise your beautiful macro pictures will require a lot of dust spot removal in post processing!

Do experiment with other materials too, like crumpled cellophane in the background. I’ve even tried materials like velvet, but found they don’t work as well as materials like card, acrylic or glass.

Once you have your studio set built, I would suggest using a tripod with your camera, flashlights with diffusers, and for ease, a wireless flash trigger.

A word of caution: photography of small wildlife subjects must be approached with extreme care not to harm or distress the creature in any way. Very often, the handling of species requires diligent expertise and experience, and in some cases a licence. So, photographing macro wildlife is not something I recommend unless you are working with a professional biologist, specialist or photographer with the appropriate qualifications.

Working with a licenced scientist and herpetologist, this image of a Caspian whipsnake was taken early morning when the snake was naturally less active. Canon EOS 1D-X, Canon EF 180mm f/3.5L Macro USM, tripod

How to light macro photography

I’m a big fan of natural light. I like shooting into low sunlight at the beginning or end of the day to backlight the subject and create silhouettes, as well as working on overcast days where clouds act like a natural softbox. This keeps everything as natural and creative as possible.

An image of a roosting common blue butterfly, taken in my garden silhouetted against natural light provided by the sunset. Canon EOS 5D Mark IV, Canon EF 180mm f/3.5L Macro USM, handheld

Cooler days are also perfect for wildlife macro photography, because the ambient temperature means that the creatures are less mobile. Even a rainy, overcast day can work perfectly, so it’s good to embrace adverse weather conditions.

In warmer weather, butterfly photography starts at dawn and ends around 9AM when the sun warms the insects and they become very active. Overcast, rainy conditions extended the time shooting with this apollo butterfly, and the overcast conditions acted like a softbox. Canon EOS 1D-X, Canon EF 300mm f/2.8L IS II USM, tripod

The most useful accessory in my bag is a reflector, which I often use to direct some nice, soft, natural light onto my subject. Reflectors are available in many sizes and colours and can be purchased quite cheaply. Alternatively, they are easy to make yourself with a piece of cardboard and some tin foil; I’ve even made them from the reflective surfaces of food packaging!

The common tree frog is an endearing amphibian, photographed here in his pond habitat. A small reflector was used to direct natural, subtle light onto the reeds. Canon EOS 1D-X, Canon EF 180mm f/3.5L Macro USM, handheld

When artificial lighting is needed, I use a range of small LED lights with diffusers, ideal because they are small, flexible and tend not to be too overpowering for small subjects. I also have a ring flash in my kit bag, not often used I must say, but sometimes useful for creating flat light, which is good for identification shots.

If you used to shoot with film rather than digital, there’s a chance that you will know about the lightbox, a lighting device that was used to view film transparencies. In the age of digital photography, these also make for good lighting devices for macro photography, particularly when shooting inanimate subjects like leaves, fruit and flowers. The subject is placed onto the lightbox and photographed from above. It’s an interesting form of lighting that creates a high-key image.

Experimenting in the early years with a lightbox. A great device for high-key macro. Canon EOS 20D, Canon EF 180mm f/3.5L Macro USM

How to make a flash diffuser for macro photography

When you buy a flashgun, it will often arrive with a diffuser, which is basically an opaque plastic cover that fits over the flash head. Using artificial flash close up on small subjects can often create harsh shadows, so the diffuser is a good option to create softer shadows.

A diffuser is simple to make if you do not have one, for example if your camera has a built-in pop up flash. Any household object can be used, like tissue paper or opaque plastic from food packaging (like the bottom of a plastic milk bottle, relish or vinegar bottle), or a document wallet for example. Cut to size so that it fits over the flash, securing into place with tape, it’s an effective and temporary solution.

How to prepare insects for macro photography

The preparation of insects for macro photography is a practice that I categorically do not engage in or recommend. We have a big responsibility not to harm, endanger or hurt any living being.

I’m aware that some photographers will make their subjects sleepy and immobile by chilling them in the fridge or even using substances like chloroform to subdue their subjects. This is a practice that I do not support – it is unethical, full stop.

So when working with insects, or any other macro creatures for that matter, especially those which are dependent on external temperature for their mobility (reptiles and amphibians for example), my advice would be to set the alarm for a very early morning wake up call, and photograph at dawn when light levels are beautiful and soft, and the insect is still roosting and naturally less active.

It’s much better to prepare yourself for the photo session, by visualising the image that you would like to achieve and getting your kit ready!

Summary

The best way to photograph insects (like this silver studded blue butterfly for example) is to get ready for early dawn shoots when butterflies are still roosting and the light is subtle. Canon EOS 5D Mark IV, Canon EF 180mm f/3.5L Macro USM, tripod

Once I dipped my toe into the world of macro photography, I never looked backed. It’s a fantastic discipline, and something that you can solely focus on, or add to your repertoire within the scope of wildlife photography.

I would suggest investing in a macro lens if you can; it should be a faithful companion to you for many years to come. And you can gradually build your kit over time (if you choose) with smaller items like a reflector, flashlight, and even extension tubes.

The world of small things is fascinating.

So, I encourage you to enjoy, experiment, and most importantly be ethical!